Black History and Archaeology of Massachusetts

- Miles Tardie

- Feb 18, 2023

- 4 min read

The legacy of African-Americans in Massachusetts is rooted in the founding events and narratives of the Northeast, but remains a neglected chapter in our history. Africans figure large in the Salem "witch" burnings, the spark of the American Revolution, and most of our national narratives - but most Americans know little. The Salem hysteria and violence against marginalized women began with accusations against Tatuba, an enslaved African brought up from the Caribbean. Crispin Attucks, who may have had Indigenous family also, is a central figure in the first skirmish of the Revolution, and the first to die.

MEAS returns to our offerings on Black Massachusetts to celebrate Black History Month

Erasure of Black Archaeology: Drowning Lands, an Intersection of Marginality

Erasure is an aspect of genocide that removes the memory, historical and visible footprint of a people from the landscape and from public discourse. Erasure comes in so many forms and is only one aspect of the events that fall under its name; erasure coincides with forced removal, land seizure, land base loss, and loss of intergenerational wealth, alongside visibility and awareness.

Here, we will examine just one form of a major mode of genocidal erasure as practiced against many vulnerable minorities in America by the power-holding Euroamerican wealth minority. We’re talking about the drowning of historically Black communities in the name of public water supply for substantially White communities of higher economic standing. The dynamics presented here in large part pertain also to post-Colonial Indigenous communities and poor rural White communities.

Read the complete article at: https://www.ethicarch.org/post/erasure-of-black-archaeology-drowning-lands-an-intersection-of-marginality

Black History (and Archaeology): "New Guinea - Parting Ways" and Blacks Who Freed America

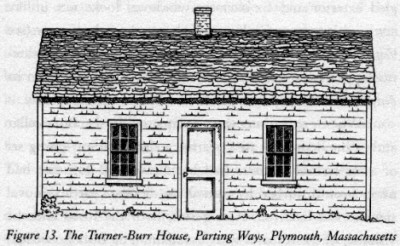

Parting Ways community was the home of four African-American Revolutionary War veterans: Prince Goodwin, Cato Howe, Quamony Quash, and Plato Turner, who were most or all slaves during that war. Quamony Quash served in the war from 1780-1783, but was not emancipated by Theophilus Cotton until 1781. Quash’s parents and more of Turner’s family also lived there.

Parting Ways is named for the fork in the road leading from Plymouth to either Plympton or Carver. In 1792 the Town of Plymouth granted approximately 94 acres those four former slaves and veterans of our independence – in return for clearing the land. The early community apparently grew to 106 acres. The place was, in fact called New Guinea at that time, which James Deetz notes is a common racial tag applied to African-American freeperson communities. According to Hutchins-Keim, the location was earlier occupied by Euro-Americans in the Fuller family.

Read more at: https://www.ethicarch.org/post/black-history-and-archaeology-new-guinea-parting-ways-and-blacks-who-freed-america

Black History and Archaeology in Massachusetts - The Fitch-Hoose House

The National Register of Historic Places recognizes the Fitch-Hoose House, an 1846 structure that was almost seized by the Town of Dalton for taxes in 2004. Standing as the last of an historic free African-American enclave known as The Gulf, the place also known as the Charles Hoose house is an important embodiment of Black History in Western Massachusetts. The Gulf refers to a local term for a low area between hills elsewhere often called a hollow, or ‘holler.’ The Crane family had earlier purchased the land that Hoos in turn purchased. In 2015, Dalton Historical Commission began renovation of the Hoose house.

Notably, as in other cases, this free African-American community was situated at the north margins of town, at some distance from the main population. Present address is 6 Gulf Road, where the site was home to generations of the Fitch and Hoose families. Dozens of African-American families lived here before and after the Civil War. Up to the 1940s, local residents say there were many African-American families living at the Gulf.

The home was humble for its time at about 158 square feet of floor space and an 8’ x 8’ bedroom, with two low-ceiling rooms upstairs, a total of five spaces, no insulation and one wood stove. The Hoose home appears as a variation on the African-American style recognized as the 12-foot house, at bit extended with added features. What might that express in the thoughts of the Hoose parents?

Available documents give only partial information on Hoose descendants. In general, the voices of Gulf community descendants is lacking in avialable narratives and reports. It appears from our search that a number of descendants could be identified and their narratives sought.

Historical Archaeology of African-American Freeperson Communities of Massachusetts

Massachusetts Ethical Archaeology Society presents a review of historical archaeology in Massachusetts of African-American Freepersons. Both on the larger scale of enclaves, and on the scale of single homes, African-American communities share many features from the pre-emancipation period through the mid-twentieth century. One common feature is locational marginality in a physical sense, accompanied by social marginality. Common threads and cultural roots have been hypothesized in the form of house plans, connecting Yoruba and African-American Freeperson traditions. The slow attrition of these communities does not appear to be well-documented or deeply studied so far. Some features of the 20th century community history suggest links to dynamics of the overall de-landing of African-American communities across the nation, especially in the Southeast.

Read more at "Today in MA:"

Black History (and Archaeology) in Massachusetts -More than a Month

African-American slaves contributed to our freedom from Colonial oppression. Through all the phases of enslavement and emancipation, African-Americans can be found living between worlds and on the margins. These communities have a story in common to tell.

Read more at: https://www.ethicarch.org/post/black-history-and-archaeology-in-massachusetts-more-than-a-month

Comments